Since I’ve been building the military police sub-section of the game, and the main military police enemy type had not been properly implemented, I figured that now was the time to remove some of my earlier programming hacks strewn throughout the entire scenario saving/loading and enemy spawning system. Unfortunately, my changes to the scenario file structure meant that I wiped out all of the previously created scenarios, but recreating them is not a particularly big timesink anyway.

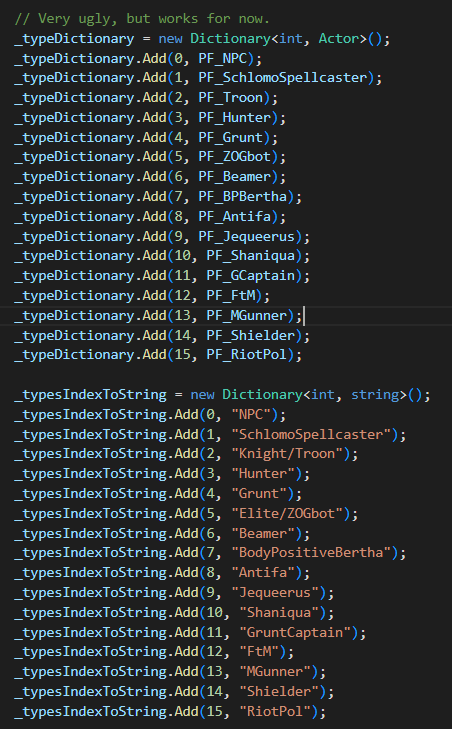

More importantly, the code for spawning in new enemies was both complicated and fragile. One part of this system required me to manually hardcode the nicknames of various enemy types into one dictionary, then cross-reference this with a second dictionary that stored prefabs. I had to remember the order of the entries in the first dictionary to read them out of the second, as well as remembering what I called these enemies in the save file, which was different than the prefab name. One wrong character in the string and nothing would spawn.

A small fraction of the old code. Terrible.

It was a fine hack when there were just a few enemy types, but had long passed its shelf life. The system was so fragile that I had even stopped implemented enemy types in game for fear of breaking something. I got to work replacing this with a more streamlined and robust system, broke the game entirely for a few days, but eventually crossed this chore off the ToDo list, and could focus on the problematic Military Police archetype.

For a lot of reasons, I have come to the conclusion that I already have too many enemy types. Most of them are far more different in flavour than gameplay. An example is the female BLM activist, Shaniqua, who twerks on the player when she gets close. It’s kind of funny the first time, and even when it stops being funny it’s good flavour, but there’s no reason why she shouldn’t just be a variation on the Reddit Admin trash mob archetype. If we’re dealing with an unimportant, currently disfavoured golem, tiny gameplay variations and unique animations are all that we need.

Having said all that, enemies are grouped together by theme in the campaign, and the police section lacked a solid, bread and butter archetype. The donut eating ZOGbots are nice to fight, but they’re modeled after the grunts from Halo. Backup dancers, not the real deal. Likewise, the riot police circling to the player is more of a supplemental enemy archetype than a mainstay, forcing the player to mix up their tactics to deal with them. The FBI agent type is a more robust main enemy, but I’m already using them in every level as something to spawn in at the end of fights and encourage the player to move quickly through the scenario. I needed something better.

Programmer art in all its glory.

Almost all enemies in the game are rock stupid. This is partly because dumb enemies tend to be eminently predictable, which allows the player to accurately plan their next moves. For some of the enemies, such as the Reddit Admins, it’s also kind of a chirp that they’re mindless followers with no cogent thoughts of their own. However, if I’m being completely honest, the main reason is simply that it is far easier to create and debug enemies with rudimentary intellect. I wanted to try my hand making the militarized police archetype a more intelligent and dynamic threat, and turned to an old favourite of mine, F.E.A.R., as inspiration.

To be clear, a lot of the “smart” AI in FEAR is smoke and mirrors. For example, the video below praises the AIs aggressive flanking maneuvers. According to the lead AI programmer, no such maneuvers existed. The AI were scripted to appear in different spots, which naturally lead to them flanking the player when they moved towards them. While this was happening, one of the replicants who was not moving would be scripted to lay down largely ineffective but very cool looking “suppressive fire” at your position.

In order to sell the illusion, special care was taken to make the replicants reply to each other in many contexts. Before the replicant moves up, they’ll say something like “moving in, cover me,” and another replicant will say some variation of “Roger.” They’ll also pair “do you have visual on him,” with a response such as “negative,” or “what’s your status,” followed by “taking fire,” etcetera.

This makes them feel like professional soldiers coordinating together, even if it’s actually a bit silly to loudly announce to your enemy everything you’re doing. While this may break basic military OPSEC, it slavishly follows the number one rule to making smart AI, which is to communicate their intellect to the audience with nary a hint of subtlety.

But it’s not all smoke and mirrors. FEAR’s AI is reasonably intelligent, and the replicants have at least the minimal coordination required to not all throw grenades or move to the player at the same time. The benefits of at least barebones coordination are obvious.

Up until now, all of the enemies in EEI are individual actors. With the exception of the riot police, and even then only for spacing, they have no knowledge of each other. An individual actor will behave the same regardless of whether they are legion, or if they’re the last man standing. This may be fine, and I didn’t need the MilPol enemy types executing genius masterplans, but I did want them somewhat coordinating their movement and firing.

One of the smallest steps to take in this direction was to make the MilPol type move to cover that wasn’t already occupied by another of their type. Again, the coordination here is not massively complicated, we just don’t want multiple enemies stupidly crowding the same spot instead of spreading out.

The first problem that we need to solve is figuring out where the enemies should be taking cover. This assumes that they don’t carry their own place-able cover. There’s nothing inherently wrong with an enemy that does that, but I focused on a type that moves to certain places in the existing arena.

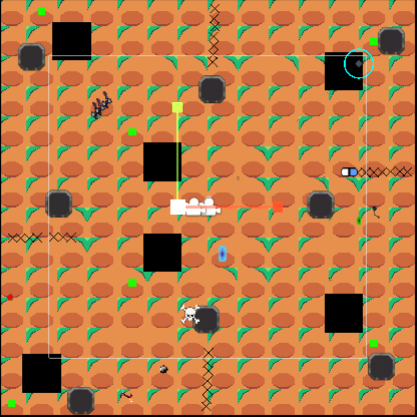

One of the most degenerate strategies in the game is mindless circle strafing. I have largely eradicated that through crude methods, but I figured that if I eased up on those solutions, the militarized police would appear intelligent by waiting in places that punish the player for circling around the outside of the arena, while also being next to something that blocks projectiles. The best spots for this are marked with the small green squares in the image below.

No idea why the pillars rendered as black squares in this screenshot.

To further add the illusion of intellect – while making them, in practice, dumber and more exploitable – they alternate between looking out both sides of the cover that somewhat face towards the center. So if you’re the player, and you can see that you’re about to move into the vision of the enemy police, you can wait a second or two and the enemy will “intelligently” look down the other side of their cover. You can then walk right up to them and beam them in the head. If you’re having a hard time following this, please reference the video above.

However, there’s one rather large problem with this scheme. Every enemy in the game has perfect information as to the player’s location. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve been behind a wall, the stupidest trash mob enemies know where you are at all times. So it’s a bit quaint that the smartest enemy in the game is checking every nook and cranny for the player when everyone else already knows.

It’s made even more odd when there are enemies that are engaging with the player right next to the “intelligent” militarized police who is “smartly” posted up, looking in some direction that is not towards the player. And it’s downright comical when the path these guys take to move to their next spot of cover takes them right past the player, who they won’t see unless you’re almost right in front of them, and to a spot where their backs are to you. I wonder what they’re thinking as they look at a stream of enemies and projectiles moving past them to the player while they intelligently sweep the area in front of them for any signs of that damn PC.

Case in point, guy mid-top. “Why are you guys all shooting at something behind me? Must be the wind.”

Taken in isolation, the behaviour of the militarized police looks smart. Taken in the context of the rest of the game it is laughably ridiculous. It looks like they’re playing with their imaginary friends.

Attach this same behaviour to a turret/sentry/robot and it would be seen as a very smart turret, because the baseline is dumber than this. But when it’s supposed to be a human behaving like this, you become very aware that you’re playing a video game. However, if that same policeman was smart enough to understand that, should he be far from the player he’ll have time to place a turret down…

The takeaway is that it is better to make a dumb enemy smart, than a smart enemy dumb. Enemies that usually behaveintelligently, but occasionally derp it up, are far more immersion breaking than enemies that are constantly stupid.

Don’t take this as me giving up on better enemy coordination, planning, and at least the appearance of intellect. This experiment didn’t quite work out, but I may in fact create that smart sentry turret item/enemy with this behaviour or something similar. Even if I hadn’t got anything tangible out of this, I’d still have learned what not to do.

One last thing. I gave these guys a firing pattern that sweeps from the edges of the arena to the middle. It was supposed to look like an intelligent action while herding the player towards the center. I didn’t take a video of this, so I hope the picture is self-explanatory.

In practice, the player will take no damage if they are quick to react and move towards the center, but they’ll only get hit with one shot, a tiny amount of damage, if they do the exact opposite. The worst case scenario is if they try to do the right thing, but are just a smidge slow to react. Since they’re moving with the sweeping line they may get hit with many shots in succession. The end result is to barely discourage circle strafing while occasionally massively punishing the player for doing what I hoped they would do.

For every ten good-on-paper ideas, about one actually works as intended.