Our last installment in this series saw Hitler making the very relevant point that people who refuse to engage in the political struggle are simply irrelevant. What he said in that last installment could be immediately applied to the More Hardcore than Hitler brigade, as if he had written it on Telegram.

Much of the book is like this, appearing almost contemporary, but there are some things particular to the exact era that the NSDAP existed. I had heard of extreme degeneracy in the Weimar Republic many times before. What I wasn’t quite so familiar with was the sheer amount of political violence. C.J. Miller’s forward to Hitler’s July, 1922 speech “Freedom or Slavery,” is quite illuminating.

Weimar Germany became an extraordinarily violent society: there were 354 political murders between 1919 and 1922 alone.

That’s an average of almost exactly one political murder every three days. While not all of those are of any real importance, it’s still incredible to think that people getting murdered for political reasons wasn’t just not rare, but was so common so as to be somewhat forgettable. And some of these were done in the middle of open succession done by some provinces.

One such crescendo took place in Bavaria in 1919–1920 as an extension of the broader German Revolution that had already replaced the monarchy with liberal democracy. In early November of 1918, tensions were already mounting. An anti-war socialist movement led by the Independent Social Democrats (USPD) was putting pressure on the government of Bavaria, which was still technically a monarchy, a holdover from a bygone era. On November 7th they held a mass rally that marched on the Residenz Palace in Munich. King Ludwig III of Bavaria and his family fled the city, abdicating the throne. USPD leader Kurt Eisner declared the formation of the People’s State of Bavaria, with himself and the USPD at the head.

Kurt Eisner

Kurt Eisner was a Marxist Jew, as were the other two leaders of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. In a tale that sounds weirdly familiar, he managed to piss off both the economic left and the social right, in addition to being seriously incompetent.

Kurt Eisner was an eccentric, a black-bearded bohemian, a drama critic, and a Utopian, with no formal administrative experience. His disavowal of Russian Bolshevik violence and extremism, and his insistence on peaceful parliamentary methods, made him unpopular with the left wing of his party and with the communists of the KPD, while his Utopianism, perceived incompetence to govern, role in inciting a munitions worker strike during the war, and acknowledgement of German war guilt drew hatred from the right. The new government, largely inexperienced and saddled with preexisting social and economic problems, was unable to function smoothly or provide basic services. The USPD was roundly defeated in the election of January 1919, but Eisner delayed and obfuscated in an attempt to hold on to his influence, refusing to call a parliament session to hand over power until credible death threats from the esoteric folkish Thule Society forced his hand.

Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley, a young aristocrat and Army officer, apparently decided to act on these death threats, perhaps in an attempt to prove himself, as he had been rejected from the Thule Society due to partial Jewish ancestry on his mother’s side. On February 21st, 1919, Anton Arco-Valley gunned down Eisner, who ironically was on his way to the parliament at that very moment to resign. The result of this was several months of complete pandemonium in Bavaria.

Anton Arco-Valley

News of Eisner’s death quickly reached parliament, where a session was underway. Erhard Auer, both a rival and colleague of Eisner as the local leader of the Social Democratic Party and minister of the interior in Eisner’s coalition government, began to deliver a eulogy. Meanwhile a devoted supporter of Eisner, the local butcher, bar waiter, and member of the Revolutionary Workers’ Council Alois Lindner, acting on a false rumor that Auer had been involved in Eisner’s assassination, stormed into parliament with a rifle and shot Auer twice. Auer’s supporters fired back, and an unfortunate Centre Party delegate was killed in the crossfire. In the chaos and confusion of the ensuing gunfight and its aftermath, parliament scattered, and was effectively dissolved.

Some pacifist fag took over and was quickly driven out by communists. And not “fuck the billionaires,” commies, we’re talking pseudo-intellectual (((coffee house communists))). Those commies were then replaced with slightly more serious commies.

The new regime was so heavily composed of literary leftist intellectuals from the hip bohemian Schwabing district of Munich that it earned the moniker “the regime of the coffeehouse anarchists.” Bavaria’s universities were opened for free attendance to anyone over eighteen, except those who wished to study history, which was declared “hostile to civilization.” A plan to collectivize Bavarian farms was announced, but never enacted. Newspapers were ordered to publish poetry instead of politics on their front pages. Other amateurish appointments included a waiter as military commissar, a convicted burglar as Munich police chief, and the highly eccentric Dr. Franz Lipp as Foreign Affairs minister, who declared war on Württemberg and Switzerland for refusing to provide him with locomotives, and in a telegraph to Lenin famously complained that Hoffmann had taken the key to the ministry toilet with him when he fled to Bamberg.

Not only do I want to quote the entire book, I want to bold the entire thing.

The Bavarian Soviet Republic was exactly what you’d expect if modern antifas took over and ran a state, without too much in the way of interference from the actual privileged class. Eventually more serious communists took over from them, and a short lived communist state was created.

They then get a sort of mini peasant rebellion from the farmers. Oven middle class people get taken hostage. Guns are confiscated (sounds familiar). The Thule Society, sort of an esoteric fascist group, starts stockpiling weapons.

Things are a mess, and the German government, which wasn’t allowed to have much of an army, hires 30,000 WWI veterans who had never bothered to stop being soldiers to go and put the communists down. That there were roving bands of mercenaries in the first place is nuts enough, especially tens of thousands of them. Entire books could be written on just these guys, and probably have been, but they’re only a piece to the insanity of Weimar.

Anyway the Freikorps, as they were called, were headed by a guy literally named Lt. General Burghard von Oven, and oven the commies he most certainly did. The Bavarian (((Communists))) had arrested some Thule Society members and then executed them along with some semi-random people, which enraged everyone even more than they were already enraged. This leads to pitched fighting in downtown Munich literally involving artillery shelling.

Hundreds of commies are killed, with hundreds more executed afterwards. The Freikorps guys kill some random civilians afterwards, mistaking them for communists, or perhaps not even caring. While that outraged the population, it was fantastic for Hitler and the nascent NSDAP, since “we’re the real opposition to those communists that you hate,” is pretty good propaganda. This was made all the better by the Freikorps guys essentially being the far more serious Proud Boys of their day.

The DAP, later to become the NSDAP, was founded during this period, but at the time it was only one group among many on the nationalist and right-wing scene. There were the esoteric folkish secret societies like the aforementioned Thule Society, nominally apolitical veterans’ associations like Der Stahlhelm (the Steel Helmet), as well as right-wing “defense leagues.” But the NSDAP and its fighting organization, the SA, were to be distinct from all of these.

Hitler specifically mocked the types of role-players “who brandish Teutonic tin swords and wear tanned bearskins, with ox horns mounted over their bearded faces,” and then “scatter when the first communist cudgel appears,” warning that no small secret society operating with cloak and dagger tactics could retake Germany, but only a mass movement. He noted that both the traditional right-wing parties and the defense leagues were lacking elements crucial to success: “The so-called national parties lacked influence because they had no force that could effectively demonstrate in the street,” while on the other hand, “the defense leagues…were masters of the street and of the state, but they lacked political ideals and goals.” Unlike these other various nationalist and right-wing groups, the NSDAP was to perfect the elusive formula for success by combining elements of folkish intellectualism, clear social policy, the street fighting capability of a mass movement to challenge communism, as well as a party-political apparatus ready to assume parliamentary seats and government posts.

Once again I find it funny how Hitler had to deal with the LARP Brigade just as we do. He also appreciated the need for both an active presence on the streets, what we would refer to nowadays as “activism,” as well as a serious political party ready to run members for office as well as organize people to take over the state bureaucracy. He recognized, as we do, that activism and electoral politics go together like peanut butter and chocolate.

Back on the topic of extreme political violence, Miller goes on to detail the assassination of the Foreign Minister of the Weimar Republic, Walther Rathenau, by some far-right members of the Organisation Consul group in a drive by shooting. To put this into perspective, that would be the equivalent of someone doing a drive by of Lloyd Austin, the current Defense Minister. Or maybe Donald Rumsfeld getting got around 2006.

The assassination was far from a random lone wolf type. They stopped a car in front of his car, and then threw a grenade into Rathenau’s car as well as hosing it down with rifle fire. Those guys were responsible for a bunch of other assassinations, including of the finance minister Matthias Erzeberger the year before.

Lloyd Austin, right. Imagine two of Biden’s cabinet members being executed.

Things got less violent in the latter days of the Weimar Republic, but political engagement remained high.

Liberal historian Richard J. Evans points to the heated political atmosphere as a bad omen for the fledgling democracy, with “every spare inch of outside walls and advertising columns…covered with posters, every window hung with banners, every building festooned with the colors of one political party or another.” He even goes so far as to suggest that during the Weimar period “people arguably suffered from an excess of political engagement.… Elections met with none of the indifference that is allegedly the sign of a mature democracy.” Liberal democracy had not been around long enough for people to be checked out and depoliticized, hardships were keenly felt, the aftermath of defeat in the First World War effected everyone, and as a result, tensions were high.

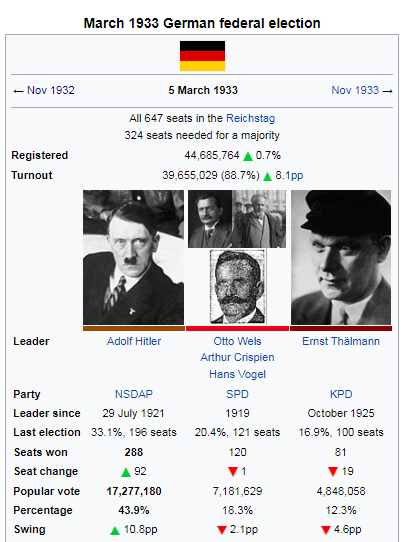

I’ve never been much of a fan for describing what can be quantified. If we look at elections in the Weimar Republic, we see near 90% voter turnout in some cases, and greater than 80% turnout in almost all others. This did not decrease with time, as the later elections had slightly higher turnout than the early Weimar elections.

The March, 1933 election, Wikipedia results screencapped above, saw almost 90% turnout. The NSDAP got almost a third of the entire population to vote for them. The Communists (KPD) themselves got about 15% of the total population to vote for them. In contrast, elections in our time often see voter turnout of less than 50%.

There are advantages to having a hugely engaged audience. It’s potentially easier to get your message out if people are already paying attention. However, the flip side of this is that we need a much smaller percentage of the total populace to support us. If we can get just 10% of the population to vote for us, that translates to 20% of the general election vote. Even more than that in some cases.

Whatever the solution, we know that it involves forming a political party and running for office.

Great article. The parallels of Weimar Germany and now are obvious.