NPR:

Francesca Gino, a prominent professor at Harvard Business School known for researching dishonesty and unethical behavior, has been accused of submitting work that contained falsified results.

Gino has authored dozens of captivating studies in the field of behavioral science — consulting for some of the world’s biggest companies like Goldman Sachs and Google, as well as dispensing advice on news outlets, like The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and even NPR.

But over the past two weeks, several people, including a colleague, came forward with claims that Gino tampered with data in at least four papers.

Gino is currently on administrative leave. Harvard Business School declined to comment on when that decision was made as well as the allegations in general.

In a statement shared on LinkedIn, the professor said she was aware of the claims but did not deny or admit to any wrongdoing.

“As I continue to evaluate these allegations and assess my options, I am limited into what I can say publicly,” Gino wrote on Saturday. “I want to assure you that I take them seriously and they will be addressed.”

I would say that “accused,” is putting it mildly. The evidence is beyond damning, in part because her falsifications – at least the ones where she got caught – were so cartoonishly amateurish. This video by Pete Judo does a great job explaining the controversy.

Francesca Gino was basically Ted Talks, The Person. She had a number of weird little hypothesis that, when studied in an experiment she had control over, always ended up coming true with overwhelming statistical significance.

(7:30)

We start off with a study from 2015. The hypothesis for this study is, in my opinion, pretty stupid. The hypothesis is that if you argue against something you really believe in that makes you feel dirty, which then increases your desire for cleansing products. But, that was what they were researching.

We start off with a cute little Just So hypothesis that already rubs me the wrong way. Theoretically there could be some link between the sensation of physical hygiene, and arguing against your true beliefs. It seems like a shot in the dark, but it might be true. Since this is an article about a Harvard pseudo-intellectual who keeps having all her shot in the dark hypotheses end up coming true with flying colours, I think you know what’s about to happen.

So this study was done at Harvard University with almost 500 students. And what they asked the participants to do was the following. Students were brought into the lab and then asked how they felt about this thing called “the Q Guide.” I don’t know what that is but apparently it’s a hot topic at Harvard and is very controversial. Some people are for it, some are against it.

The students either said they were for or against it. Then the students were split into two groups. Half the students were asked to write an essay supporting the view that they just gave. So if they said “I’m for the Q Guide,” they had to write an essay explaining why they were for the Q Guide. But then [the other half of] the participants were asked to write an essay arguing opposite the view they just gave.

Again, the idea being that those who are writing an essay against what they actually believe in would make them feel dirty. Because after they had written the essay they were then shown five different cleansing products, and the participants in the study were asked to rank how desirable they felt these cleansing products were on a scale of 1-7, with 1 being completely undesirable, and 7 being completely desirable.

Stop for a minute, and ask yourself what this study could possibly prove.

All studies, even the ones that have non-fraudulent data, can only show what happened in the study environment. Part of that involves the subjects knowing that they are a part of a study. This can have massive implications, especially for psychological studies. Once people know they are being watched their behaviour will undoubtedly change. For instance, I would not be surprised if people in both groups tell the researchers that they really like the soaps so as to come across as more hygienic.

Even if Gino’s hypothesis – that arguing against your real position makes you really like soap – was true, this is such an off the wall hunch that we would expect to find a very small effect. With a study size of just 500, it would be very difficult to conclusively prove that any discrepancy between the two groups was due to more than random chance.

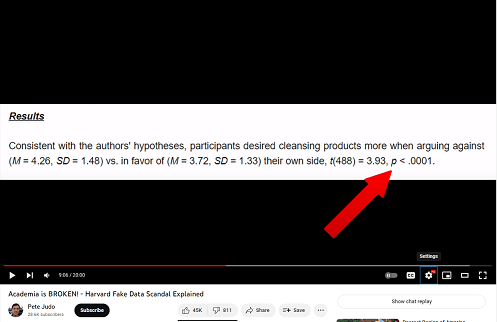

And again, the authors found a strong effect. You can see here that the P value is less than 0.0001.

Yet her team knocked it out of the park, conclusively “proving” that arguing against your position makes you want cleaning products.

Yet her team knocked it out of the park, conclusively “proving” that arguing against your position makes you want cleaning products.

So the [investigators of Francesca Gino] managed to source the data online, and they found some weird demographic errors. This is very common in studies. The subjects have to give some demographic data about themselves, which gives the researchers more flexibility when cutting up the data later on.

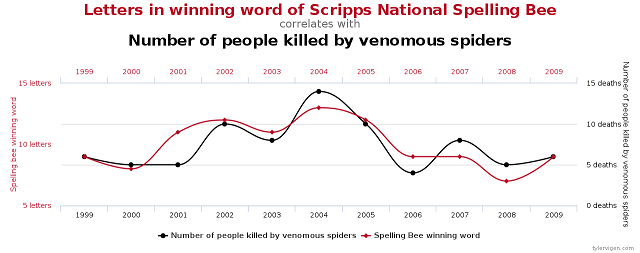

It also lets them do something called “p hacking.” Think of it this way. You look at the students overall. Then you look at the freshmen, then sophomores, then juniors, then seniors. Then you break it down by race. Then you break it down by degree. Keep doing this, even combining sub-groups into further sub-groups, and you have a much better chance at (spuriously) finding your hypothesis to be true, provided you only look at Nigerian female sociology majors in their sophomore year.

But that’s not what happened here. What happened was Gino and Co just straight up faked the data.

…

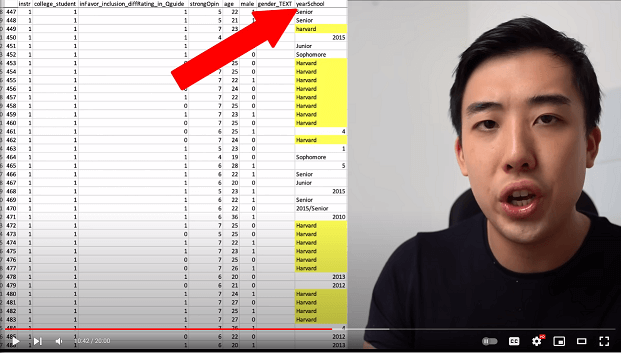

Number 6 [of the demographic data] was what year they were in school. Now the way this question is structured isn’t very good in terms of research design. Nevertheless there are a number of acceptable answers you can give. Because Harvard is an American school you might say “I’m a senior,” or “sophomore.” You might write down the year you were going to graduate. Or you might write down a 1, 2, or 5 to indicate how many years you’ve been there.

These are all different answers, but they all make sense. That’s what our vigilantes found, a range of different answers which were all acceptable, except for one. There were twenty entries in this dataset where the answer to the question “what year in school are you,” was “Harvard.” That doesn’t make any sense.

And the other thing that was suspicious about these “Harvard” entries was that they were all grouped together in 35 rows. This was a dataset of nearly 500 participants, and yet all these “Harvard” answers were within together in 35 rows.

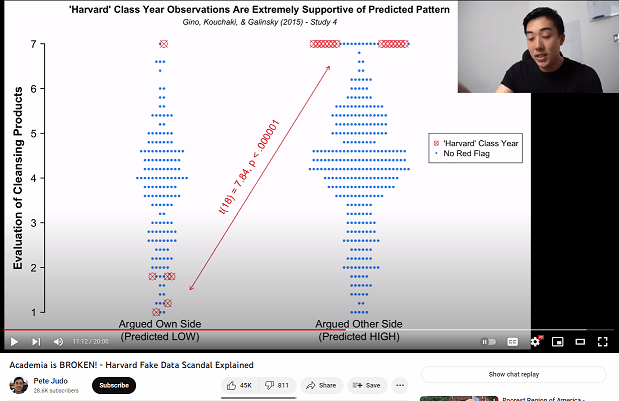

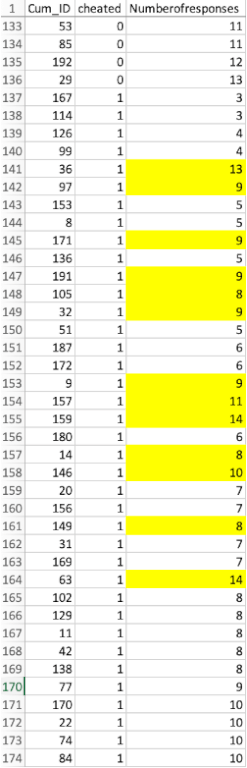

Our vigilantes treat these “Harvard” answers as suspicious data entries. They mark them in circles with crosses. And you can see that the ones that are suspicious are the most extreme answers supporting the hypothesis of the researchers.

It is genuinely stunning how obviously fraudulent these entries are, especially when looking at the “argued other side,” half. All of the “Harvard” entries which were forced to argue against their stated position were like “OMFG I love all these soaps just like Francesca Gino predicted I would!”

This isn’t even the most amateurish data forgery that she did. There was another study where they were testing Gino’s hypothesis that cheaters were more creative. Subjects flipped a coin, were told that they would be given $1 per heads with no need for proof, then were asked how many times they got heads. Right after this they were, to quote the study “asked to generate as many creative uses for a newspaper as possible within 1 min.”

There are a ton of methodological issues with this. Here are just a few that popped out at me. First, people who cheat while knowingly part of a study are not necessarily the same as people who cheat more in day to day life. Second, I could see how cheating could provide a visceral thrill which serves as a stimulant and gets your brain more dialed in, which would only be a short-term effect. Third, there is no judgement with respect to the utility of the various uses for the newspaper, so someone who comes up with ten garbage uses would score higher for “creativity” than someone who comes up with three legitimate uses. Fourth, someone like me might cheat if I got screwed out of some heads, but be a committed anti-cheater on other, less arbitrary and random aspects of life.

Even if the data wasn’t faked, you can’t “find” that cheaters are more creative with a study design this poor. That’s a moot point anyway, since DataColada, the vigilantes, clearly show that there are a bunch of entries that are completely out of order, seemingly added in after the list had already been sorted.

What happens when we remove these seemingly odd entries?

The found effect totally vanishes, and cheaters appear no more creative than non-cheaters.

Fransesca Gino

Her fudging of the data is somewhat less stupid than it appears at first glance. It’s sorted first by subject ID, then cheating times, then newspaper uses. She couldn’t add new entries to the list, so she had to semi-randomly progressively bump up the newspaper uses count for the cheaters as she went along. As long as no one ever looked at the data, she was fine.

Which brings us to the real story. Why the hell did no one ever look at the data?

Here we have a prominent Harvard Professor who is famous for having all these quirky little hypotheses that get “found” to be overwhelmingly accurate in nearly every study she’s ever conducted. She’s been doing this nearly two decades, and been a professor at Harvard since 2010. You’re telling me that there were no competitors who wanted to take a bite out of her ass until now? For a supposedly competitive field, these psuedo-intellectuals sure don’t seem to enjoy actually competing against each other.

As an aside, I found a course she was offering on LinkedIn promising to get rid of your toxic workplace behaviours. I didn’t even know that LinkedIn offered courses at all, and while I didn’t see anything anti-White or particularly perverted, they did use this faceless collection of corporate mystery meat as the identity of a productive and happy work environment. I’m quite sure she had all the requisite (((politics))) to succeed in this field.

NPR:

Gino has contributed to over a hundred academic articles around entrepreneurial success, promoting trust in the workforce and just last year published a study titled, “Case Study: What’s the Right Career Move After a Public Failure?”

Francesca Gino has been caught four times. Presumably she faked the data more convincingly on numerous other occasions.

It also puts into perspective the downplaying of the “reproduction crisis.”

Is psychology facing a ‘replication crisis’? Last year, a crowdsourced effort that was able to validate fewer than half of 98 published findings1 rang alarm bells about the reliability of psychology papers. Now a team of psychologists has reassessed the study and say that it provides no evidence for a crisis.

“Our analysis completely invalidates the pessimistic conclusions that many have drawn from this landmark study,” says Daniel Gilbert, a psychologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the reanalysis, published on 2 March in Science2.

But a response3 in the same issue of Science counters that the reanalysis itself depends on selective assumptions. And others say that psychology still urgently needs to improve its research practices.

Harvard psychologists say that there’s no such thing as a reproduction crisis in psychology, provided that you use their selective assumptions, cherrypicking, and statistical shenanigans. It might also help when you fake the data in the same way they do. Maybe get them on the phone before you publish your results to see if they can help you with that.

Harvard is Hebe Central – even worse than UC Berzerkely – which the Hebe fake PhD’s direct from ellis island founded – same time they “founded” the bullshit field of “Psychology”.

And that is one ugly woman with a big fake smile.

I’m having something of a reproduction crisis myself.

If that name is unironic You’re in the wrong place.

Looking at how White the men who took her down look… Jews are going to have to remove a lot more White men from academia if they want to see their vision of “truth is only true if schlomo says so” come to pass.

“Part of that involves the subjects knowing that they are a part of a study. This can have massive implications, especially for psychological studies.”

There is even a phenomenon in experimental psychology for a bias that can result from this, known as demand characteristics. Basically, demand characteristics describes whenever the test subjects are able to figure out what the experimenter’s desired outcome is (either indirectly, or in more egregious cases, through direct coaching), and so the test subjects will effectively start larping instead of actually carrying out the experiment.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is perhaps the most infamous case of demand characteristics rendering the results completely worthless. Philip Zimbardo, the researcher who conducted the experiment, had always claimed the following two things of his experiment:

i) the guards were never coached on how to treat the prisoners;

ii) the prisoners could leave any time they wanted by saying “I quit the experiment.”

Around 2017, French researcher Thibault Le Texier actually went to the Stanford archives and was able to prove that both claims were false. There were recordings of briefing sessions in which some of the guards were criticised for “not being brutal enough”, and the phrase “I quit the experiment” was nowhere to be seen on any of the consent forms signed by the people who volunteered to be prisoners. The whole experiment was essentially designed to produce the outcome that it did, so that Zimbardo could use it to push a political agenda (the abolition of prisons).

The same could also be said of the Milgram experiment. The little-known fact is that most test subjects were actually able to figure out that they weren’t really delivering electric shocks to a person, so they just played along because they knew that nobody was actually being harmed. Also, the experiment went through multiple revisions before any results were published – in one of earlier versions of the experiment the compliance rate among test subjects was zero.

I remember that FTN deep dive. It was eye opening.

Had no idea Jazz’nds did one – I stumbled upon it all by myself. Doesn’t surprise me that he did one.

[…] AcademiaLand: Harvard Honesty Researcher Professor Francesca Gino Put on Leave for Rampant Research … […]