Cooper back with another piece. As always, the quote indentations are my commentary, unless directly underneath a link. And please follow Cooper on Telegram here to get updates on Honkey Night in Canada.

As violent crime mounts in Canada’s urban centers, comments usually reserved for boomer groups on facebook are becoming commonplace. Arrests of sought-after thugs elicit a hand wave along with “He’ll be back on the streets shortly”. Most recently, judge Maria Sirivar has been treating the alleged, black killers of Ken Lee with OJ gloves, allowing some their freedom and use of the internet. The three girls denied bail thus far were forced into “open custody”.

“There are open and secure youth custody facilities.

Open custody youth facilities are generally smaller residences located in the community where youth can have access to staff supervised programming in the community.

Secure custody youth facilities are generally larger sites, which have higher security measures (for example, fences around the property) and youth access to the community is generally facilitated only where approved.”

That’s right, they’re going to a group home.

This lenience should come at no surprise. Sirivar “is a founding member of the Sanyu Youth Foundation”, according to this site, and has worked with “at-risk youth” internationally. I could not find this specific organization but groups with “Sanyu” in their name are mostly based in or centered around Africa. When appointed as a provincial justice Sirivar said “this appointment is not about me as an individual, but rather somebody that looks like me” (she is black). This comment shows the judge to be racially aware. Her handling of this case is a conflict of interest, though not necessarily an unintended one.

Judge Maria Sirivar

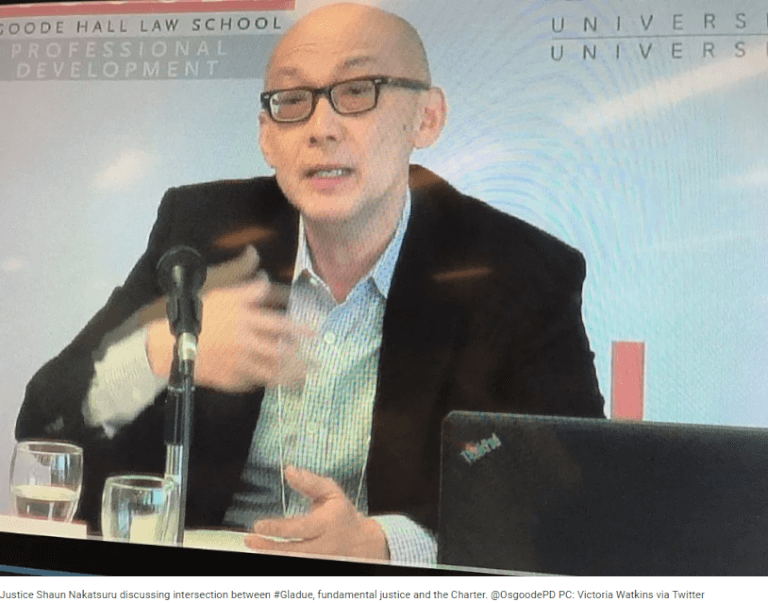

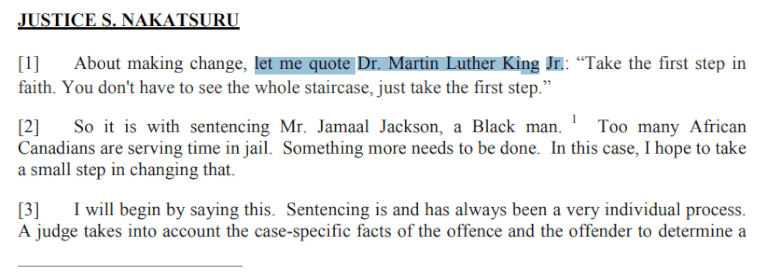

Overrepresentation of blacks in prison has long been a concern for activists, but it has taken a backseat to native issues until (I feel) very recently. What I have been worried about is how the incessant breaks given to indigenous offenders could carry over to blacks. No greater proponent of this extension can be found than Justice Shaun Nakatsuru.

Nataksuru is of Japanese descent and has earned a moniker: “the poetic judge”. This is due to his “empathetic” treatment of offenders, a characteristic that supersedes the rights of victims and the public at large. For example, the judge released a Mohawk man who could not post bail because no one would vouch for him. Nakatsuru attributed his decision to addressing “the evil that is the over-incarceration of indigenous people”. The defendant, Pawel Sledz, was accused of participating in a gang rape.

The “justice” in question, Shaun Nakatsuru.

In a preceding case, R. v. Armitage, the judge forced the legal community to take notice by issuing a ruling “in a style resembling a diary entry”. It was essentially a 15-page love letter to the guilty party, excusing his criminal history by way of his racial background. Commenting on the decision and its “simple language”, lawyer Steven Benmore had this to say:

“I think he jumped 10,000 feet up into the air and said ‘Hey world, we actually touch a lot of people with our decisions, and I want to touch Jesse. I want to touch the entire community Jesse comes from. And I want to touch Ontarians, and show them that we in the legal services, the judicial system, we care about people’”.

This has become Nakatsuru’s go-to format for sentencing decisions.

Both the Sledz and Armitage cases were adjudicated prior to the Poetic Judge’s appointment to Ontario’s Superior Court. On his application for the job, we can see plenty of race-based accolades. As follows:

Continuing education

- Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice Annual Conference, Aboriginal Law, October 2015, Saskatoon

- Special Ontario Court of Justice Indigenous Peoples Conference, June 2016

Legal Work Experience

- 2006-present: Justice, Ontario Court of Justice, Toronto Region. Provincially appointed judge conducting criminal trials and provincial offences appeals. Main areas of expertise are criminal, constitutional, and regulatory. I have considerable experience in Indigenous persons’ court.

Other professional experience

- 2013 to present: Judicial Coordinator of the Gladue Court

Teaching and continuing education

- Speaker, “Race and Cultural Difference Bridge,” University of Toronto Law School, 1997-1998

- Panelist, “The Strength of Diversity,” Federation of Asian Lawyers Conference, November 7, 2009, Toronto

- Moderator, “Aboriginal Justice Systems and the Charter,” Fourth National Conference on Aboriginal Criminal Justice Post-Gladue, Osgoode Hall Professional Development, April 26, 2013

- Panelist, “The Gladue Court,” Criminology class, Ryerson University, March 25, 2015, Toronto

- Speaker, “A Small Path to Reconciliation,” Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice Annual Conference, October 16, 2015, Saskatoon

- Moderator, “Gladue and First Responders,” Ontario Court of Justice Summit on Gladue, June 8, 2016, Toronto

- Panelist, “Enforcement and Racialized Communities,” Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers, October 29, 2016, Toronto

- Panelist, “Gladue Process,” Gladue Summit by the Ministry of the Attorney General, November 29-31, 2016, Thunder Bay

*Keep in mind that “- present” is as of his application in 2017.

NOTE: The application is quite long. If you want to check it, I’d recommend ctrl+f’ing what Cooper wrote above. But yes, it’s as bad as it looks. And this is what he puts forwards as qualifying himself for the job, because this is what the (((judicial system))) wants to see.

Doubters may say that I am being selective in my reading of Nakatsuru’s resume. Others may posit that this is standard stuff for any judge. To the second bullet: okay that just proves that racial activism has infected the entire judicial system. To the first point: let’s look into Nakatsuru’s comments on the application itself.

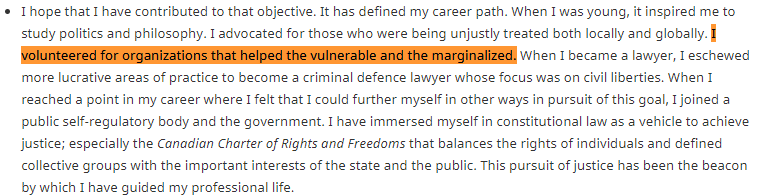

He takes great care to explain his passion for remedying “injustice and unfairness”, explaining that this drove him to delve into politics and philosophy as a young man. He stood up for “those who were being unjustly treated”, “the vulnerable”, and the “marginalized”. His area of expertise as a defence lawyer became civil liberties, though he later turned to constitutional law. Specifically, he believes in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and its means to “achieve justice”.

Normally I hate screencaps, but the occasional one, with a link provided, can be useful. Again, the application is here.

As the questionnaire attached to his application drags on, we start to see exactly what Nakatsuru means by “justice”. He lauds Canada’s “diversity and its reputation for tolerance of difference”. Of course, this reputation is stained with the scars of past racism, including his family’s WWII internment. He feels that this experience with “generational trauma”, and his life as a visible minority member has allowed him to relate to other non-Whites. He says that this common thread “has been valuable to [him] in [his] decade of judging”. Nakatsuru describes many of his clients with the buzzwords from earlier in the text (“vulnerable”, “marginalized”, “visible minorities”). Toronto is extolled as a capital of diversity, which, in Nakatsuru’s mind, improves it greatly (stay tuned for the great irony of this notion). He then confirms his ties to “organizations that promote racial and social equality”.

The next bits of interest come in Nakatsuru’s answer to questionnaire section three: “Describe the appropriate role of a judge in a constitutional democracy”. An independent judiciary is of utmost importance to Nakatsuru. He acknowledges that “strictly speaking, judges do not create law”. A moment later, we see an about-face:

“On the other hand, a positivist view would recognize that judges do fashion the law to a certain degree. In other words, the judicial role in its effect, albeit perhaps not its purpose, may encroach into what is perceived as law-making.”

Nakatsuru does use careful language to soften this (“whatever the reality of the view…”) but he has played his hand. His constitutional views lay this bare.

“…the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has expanded the role of the judiciary. This expanded role is not without its critics. That said, it is now a constitutional responsibility vested in the courts. It is a responsibility that cannot be ignored. It is a power that must be wisely and prudently exercised…our constitutional order requires judges to protect individual rights and freedoms from undue encroachment by the state or oppressive wishes of the majority…History teaches us that minorities and those out of favor with then prevailing majority attitude can sometimes be best protected by constitutional documents that are interpreted, applied, and enforced by an independent and vigilant judiciary”.

Michael Tammen

Essentially it’s “Kritarchy: Unchained.” Or “The Robed Dictatorship,” if you would prefer. Never was that made more clear to me than sitting in the Rob Hoogland trial, when the “justice” pictured above, Michael Tammen, whined for forty five minutes about “our democracy,” before fucking over the lowly peasant.

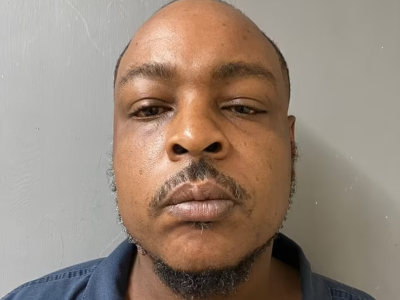

As noted, Nakatsuru’s race-training has focused on native issues, mostly in the context of Gladue principles. In the case of R. v. Jackson, this would change. Jamaal Jackson is a habitual offender with convictions dating back to 2000 (including violent crimes and robberies with weapons). In 2018 he was found guilty of buying and possessing a loaded pistol while under several firearm restrictions related to previous offences.

When sentencing Jackson, Nakatsuru invoked both Martin Luther King Jr. as well as “To Kill a Mockingbird”. These references were linked to emotional appeals of perceived anti-black racism. In fact, much of the sentencing decision is focused on Jackson’s race and how it somehow explains his rampant anti-social behaviour. The judge also cited a case that dealt with whether Gladue principles should be extended to offenders of african descent (R. v Borde). It was decided in said case, that, no, the Gladue framework applies to Canadian natives only. However, R. v. Borde, and other decisions mentioned in R. v. Jackson “acknowledged” racism to be an exacerbator of black criminality. This door left ajar would be swung wide open by the Poetic Judge.

No really, he did that. You can see the document for yourself here.

In section G. of his decision, Nakatsuru stated that colonialism, residential schools, etc. make the indigenous experience unique to that of black Canadians. Therefore, the issue of black over-incarceration cannot technically be addressed “by simply layering a Gladue template on top”. However, just a few paragraphs later (s. 73), Nakatsuru expresses that he can use existing sentencing principles to combat this very issue. He then refers to the very section of the criminal code (s. 718.2e) that contains the basis of the Gladue principle itself (!).

“[79] It is the remedial nature of s. 718.2(e) that provides the authority for me to address the disproportionate imprisonment of african Canadians. While Parliament did single out Indigenous persons for special attention, its enactment benefits all offenders. For african Canadians, given the evidence presented to me, disproportionate incarceration is an acute problem. Section 718.2(e) can be resorted to in order to address this particular problem. It is further meant to encourage restorative approaches in the application of the sentencing principle of restraint. “

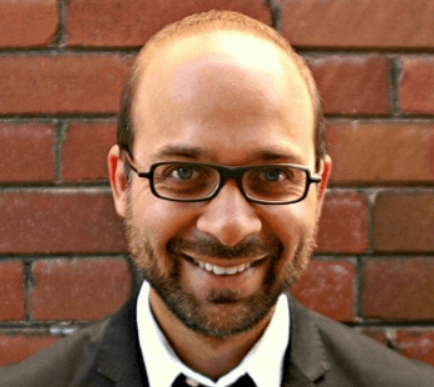

The crown sought 8.5-10 years of imprisonment for Jackson; he was sentenced to 6. Further covering himself, the judge wrote “this is not a race-based discount” (s. 176). This claim is categorically false. The write-up was met with much fanfare from progressives, with one Osgoode Hall Law School professor, Faisal Bhabha, calling it “remarkable on many levels” and “a game changer”. Despite Nakatsuru’s suggestions to the contrary, thecourt.ca wrote that he “utilized a Gladue framework”.

Faisal Bhabha

As an aside, I found an unintentionally funny piece written by Faisal Bhabha, where he extremely tepidly defended the Palestinians, and then had the B’Nai Brith calling for his “human rights professor” job to be holocausted. It’s good stuff, but it belongs in a different piece.

Had this been an isolated case, one could see the public being frustrated. But the real problems with Common Law are the ripples each decision creates. In 2014, Kevin Morris was approached by Toronto police in connection with a home invasion/assault committed earlier in the day by a group of black men. It would turn out that Kevin and his friends were not the men involved. However, Morris elected to immediately flee from the cops and would later be found to have carried a loaded, illegal handgun when he did so. Morris was sentenced by Nakatsuru in 2018. The judge referred to his own decision earlier that year in R. v. Jackson. While the crown asked for Morris to serve 4 – 4.5 years, Nakatsuru settled on 15 months’ jail time, minus 3 months for “charter violations”. After credit of 1.5:1 for pre-trial custody, it was decided Morris should serve one day in jail followed by 18 months of probation.

In the written decision the judge decided to “in before” accusations of being soft on crime. He explained how the regular occurrence of gun crimes had rocked the citizenry at the time. Nakatsuru immediately dismissed the notion of securing public safety in favour of mitigating the jailing of blacks. He even agreed that these sentiments were clearly at odds.

“Sometimes the solutions to these two problems may seem to clash with each other. Gun crime calling for stiffer punishment. Longer jail sentences. The other problem calling for more moderation. More restraint”.

Nakatsuru, as in the Jackson case, chose the latter. He painted Morris as a man held down by anti-black racism, profiled by teachers and the police alike. Ironically, Morris was also described as someone who feared walking in certain neighborhoods due to his own past victimization (being stabbed) by other blacks. This violence was also attributed to systematic factors.

Two reports were presented by the defence during Morris’ sentencing, one addressed so-called anti-black racism in Canada; the other explained Morris’ personal history (as an example of how such oppression shaped his nature). Both were accepted by the court. Their authors were three black racialists. As per his usual style, the sentencing decision’s format was a heartfelt letter to Morris. He expressed deep sympathy for the man on trial:

NOTE: This starts on page 11.

“However, Ms. Sibblis noted that you have regret about the choices you have made. You feel bad about the pain it has caused your mother. I also noted your testimony before me. There was a moment on the stay application when you could not carry on testifying. We had to take a break. I believe you were overwhelmed in that moment. I could see that. From everything that I know about you, from your conduct at trial and from the information given to me at this sentencing, you are far from a hardened criminal. All of this is felt very deeply by you. I believe that you have real regret for your actions. It is not regret getting caught or being punished. It is remorse for choosing the path that you did”.

This is even though, between the original crime, and this decision, Morris had been arrested again on charges relating to a home invasion robbery (he would be found guilty in 2019).

In 2021, Nakatsuru’s decision was appealed. If the significance of this case was in question, one need only to examine the numbered list of interveners, including representatives from the David Asper Centre, Black Legal Action Centre, etc. Almost all intervening parties were associated with anti-White organizations. In their appeal the crown posited that “the trial judge allowed his consideration of the impact of overt and institutional racism on Mr. Morris to overwhelm all other considerations relevant to fashioning a fit sentence.” The proper sentence should have been three years. Though the crown asked the court to vary the sentence, it was also said “the incarceration of Mr. Morris at this time would be inappropriate”. Therefore, the imposition of said sentence should be permanently stayed (meaning Morris should not serve the jail time that he deserved). Why? Morris, after serving jail time for the 2017 home invasion, had been paroled.

The crown did not fight for justice in this case, and the court of appeal reiterated the same racial excuses when commenting on the circumstances of Morris’ crime.

The Crown throwing the fight is extremely common. Just recently they did the same with the White woman murdered by security at a hospital in Ontario. And of course, church burnings, antifa terrorism, the list goes on.

The appeal was successful, in that the sentence was varied to two years, but was permanently stayed, as the crown was all too happy to allow. Nothing of substance was really achieved; in fact, things got worse. I point to this section of the appeal court’s write-up.

“[123] Although we would not equate Black offenders with Indigenous offenders, for the purposes of s. 718.2(e), the Gladue/Ipeelee jurisprudence can inform the sentencing of Black offenders in several respects: see Borde, at para. 30. Just as with the discrimination suffered by Indigenous offenders, courts should take judicial notice of the existence of anti-Black racism in Canada and its potential impact on individual offenders. Courts should admit evidence on sentencing directed at the existence of anti-Black racism in the offender’s community, and the impact of that racism on the offender’s background and circumstances. Similarly, in considering the restraint principle, courts should bear in mind well-established over-incarceration of Black offenders, particularly young male offenders. Finally, as with Indigenous offenders, the discrimination suffered by Black offenders and its effect on their background, character, and circumstances may, in a given case, play a role in fixing the offender’s moral responsibility for the crime, and/or blending the various objectives of sentencing to arrive at an appropriate sanction in the circumstances.”

NOTE: It drives me up the wall when these anti-Whites simply sneak in the premise that Blacks are “over-incarcerated.” No, they’re probably under-incarcerated, they just commit a lot of crimes. Also, notice how they never say that men are “over-incarcerated,” despite being imprisoned at twenty times the rate of women.

This is a parroting of Nakatsuru’s language. We don’t do black Gladue stuff here, except when it’s applicable. When is it applicable? Every time!

The Morris Decision was used as a sentencing basis recently in R. v. Stewart (December of ‘22). Having just turned 19, Shaquane Stewart was running from Toronto police in 2018 when he discarded a loaded handgun in a schoolyard. It was found the next morning, with both an entry door and play structure close by. While judge Jill Copeland, did not write a “dear Shaquane” type of sentencing report, she did heavily cite the precedents discussed earlier in this piece. The result?

A conditional sentence of two years less a day. A year of house arrest, followed by curfew for the year remaining. Stewart told Copeland that he wanted to break the cycle of crime brought about by the violence he saw regularly in the projects he was raised in. He wished to be there for his young son, so the boy could be “a good man, probably a basketball player”.

Lo and behold, Shaquane Stewart is back behind bars as of February 3rd, 2023. Not only was he caught carrying another loaded handgun, but the cops also found 122.8 grams of “suspected” cocaine in his apartment.

B-b-but he a gud boi. He wanna be der for dem keedz and teach dem to be da baskeball peepol.

What do these developments in case law mean for officers trying to target the marked increase of gang-related murders (committed in cities dominated by black and native criminal organizations)? How will they affect those accused of murdering Ken Lee?

Rather than worrying about black incarceration, the Courts should focus on black crime. If so-called progressives like Nakatsuru are hell-bent on transforming the law to suit their socio-political agenda, it is up to those with an iota of common sense to straighten things out. This type of racial preference should go up the chain. If blacks are allowed to get away with this level of public hazard, let the Supreme Court say so. Let them tell it to the whole country. But alas, this can’t happen when local judges and appeal courts are complicit in the whole game.

Excellent article from Cooper. This fits in very nicely with an upcoming piece of mine wherein I detail the explicitly anti-White rulings that we’ve seen from all across Canada. This is very much not constrained to one judge in particular, it is an infestation.

Coming soon.

In my very humble opinion, the legal profession is completely out of control in this country.

Lenient judges/prosecutors have a great legal make-work scam: capture and release thugs, who will re-offend as sure as night follows day, and who will then repeatedly require expensive lawyers and judges ( I repeat myself) and other legal services. For additional laughs, complain about how underfunded the justice system is.

These lawyers have to eat, by God, and right now they feast on the taxpaying public.

Anyhow, “justice” according to lawyers is really about “just us.”

I couldn’t read this because it makes me want to puke. This judge should just go get fucked by a nigger already he loves them so much. I would support a true defunding of the police, to the point there are no police, that way we can just lynch the nigger criminals, and there is nobody to come arrest us for it.

The local TV networks in Ontario are doing a full court press on this topic claiming blacks and other groups are somehow oppressed by “systemic racism” because they end up in prison more often, never discussing relative crime rates of course and even though the actual system is comprised of activist judges, lawyers and other trash who give them sentencing discounts or let them free for serious crimes, and by corollary given that they’re ideologically trained like this, they probably throw the book at at the great white defendant.